|

|

|

|

Turkey,

Georgia and Azerbaijan |

|

|

|

|

Sunday,

May 27th. Ashgabat, Turkmenistan. We're slowly but surely

progressing east. We left Istanbul on the 1st of May, heading

for Cappadocia. Our initial plan was to ride along the Black

Sea Coast, but after seeing pictures of the region around

Goreme, with its suggestively shaped rock formations, we decided

to make the detour. Ellen had found a little hotel built into

a rock, offering a so-called Honeymoon suite, complete with

a Jacuzzi, for a very reasonable price. We stayed there for

three days, wandering and driving around the region, trying

to find the best angles to take pictures of monasteries and

phallic rock outcrops. (The pics will be available soon, we're

having trouble finding fast connections).

Sunday,

May 27th. Ashgabat, Turkmenistan. We're slowly but surely

progressing east. We left Istanbul on the 1st of May, heading

for Cappadocia. Our initial plan was to ride along the Black

Sea Coast, but after seeing pictures of the region around

Goreme, with its suggestively shaped rock formations, we decided

to make the detour. Ellen had found a little hotel built into

a rock, offering a so-called Honeymoon suite, complete with

a Jacuzzi, for a very reasonable price. We stayed there for

three days, wandering and driving around the region, trying

to find the best angles to take pictures of monasteries and

phallic rock outcrops. (The pics will be available soon, we're

having trouble finding fast connections).

Attractions

in the region are many : Whirling dervishes (based in Konya

in western Turkey, the whirling dervishes are a sect that

believes in spinning around in circles as a means to spiritual

enlightenment), underground cities dating back 4,000 years,

countless monasteries and pleasant people, despite the ever

growing numbers of tourists in the region.

We

headed on, off the main roads, into one of Turkeys many mountain

ranges. The weather continued to be rather nasty, the roads

were very potholed and tourist presence completely ceased.

In a village called Sebinkarahisar, we spent a very pleasant

evening with a local teacher we met by chance, and a local

cook, who was informed of our arrival by the other villagers

and sent after us because he spoke German and English. He

said we were already the second tourist party this year. What

a lively place.

We

headed on, off the main roads, into one of Turkeys many mountain

ranges. The weather continued to be rather nasty, the roads

were very potholed and tourist presence completely ceased.

In a village called Sebinkarahisar, we spent a very pleasant

evening with a local teacher we met by chance, and a local

cook, who was informed of our arrival by the other villagers

and sent after us because he spoke German and English. He

said we were already the second tourist party this year. What

a lively place.

Both on

and off the main roads, stopping for gas usually lead to a

Question and Answer session accompanied by lots of tea and

good wishes. At least they let us pay for the gas. If one

measure of hospitality is the little gesture of offering tea

to passing strangers, Turkey certainly is one of the most

hospitable countries we've encountered so far. We arrived

in Trabzon, on the Black Sea, for an uneventful stay agreeably

punctuated by a somewhat strenuous (lots of walking!!) visit

to yet another monastery, Sumela, spectacularly situated high

up inside a mountain wall.

From Trabzon,

we rode into Georgia. The border crossing was fairly painless,

taking about one hour and a half, and costing $3 per person

and $10 per bike. We had been warned about corrupt border

guards and police in the region but we hardly had any trouble.

We did have to pay once, a probably bogus transit fee, and

several of the countless cops that stopped us looked like

they were really good at extorting money, but we got away

lucky. Lots of smiles and saying in the friendliest voice

possible repeatedly in Luxembourgish : "No way, meathead,

you're not getting any money" generally works.

The

Georgian Black Sea coast was a favourite vacation spot for

apparatchiks during the Soviet Era, and the seaside is filled

with derelict hotels in the familiar Soviet style, or rather

absence of it. Other remnants of that legacy are huge industrial

complexes, now left to rust in the middle of otherwise beautiful

landscapes.

The

Georgian Black Sea coast was a favourite vacation spot for

apparatchiks during the Soviet Era, and the seaside is filled

with derelict hotels in the familiar Soviet style, or rather

absence of it. Other remnants of that legacy are huge industrial

complexes, now left to rust in the middle of otherwise beautiful

landscapes.

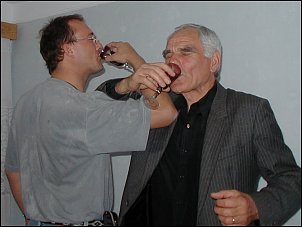

We spent

a couple of days in Kutaisi in western Georgia, where we were

introduced to the notion of Georgian hospitality by Lali and

Zouri, our hosts : While Lali tried to force us to eat every

dish she knew how to prepare, Zouri made an attempt at killing

us with kisses and homemade wine. He was very impressed with

the only Georgian word I knew: "Bolomde", which

means, "bottoms up". I had missed a great opportunity

to shut up, as for the rest of the evening, he honored my

linguistic skills by finishing his toasts (an old, honored

and very dangerous tradition in Georgia) with precisely that

invitation. Although women are theoretically exempt from having

to participate in that particular custom, Ellen ignored the

exemption and tried to help me defend the honour of all foreigners.

The following day is best erased from memory for the most

part. When we had finally mustered the courage to get up and

explore the town, we met Maher, a Syrian entrepreneur who

took p! ity on what was left of us, showed us the sights and

helped us forget our misery.

Next

stop was the capital, Tbilisi, where we indulged in the things

you can only do in capital cities in those parts, movies,

shopping, Internet and pints of Guinness. As the days progressed,

we learned more and more about Georgian wine : There are several

hundred varieties of grapes in the region, and the Georgian

word "ghvino" might very well be at the origin of

the word "wine" as we know it, since Georgia is

perhaps the oldest known wine growing region in the world.

Maybe that explains why they can drink it like water, while

unsuspecting tourists fall like flies after a meager three

litres or so.

Next

stop was the capital, Tbilisi, where we indulged in the things

you can only do in capital cities in those parts, movies,

shopping, Internet and pints of Guinness. As the days progressed,

we learned more and more about Georgian wine : There are several

hundred varieties of grapes in the region, and the Georgian

word "ghvino" might very well be at the origin of

the word "wine" as we know it, since Georgia is

perhaps the oldest known wine growing region in the world.

Maybe that explains why they can drink it like water, while

unsuspecting tourists fall like flies after a meager three

litres or so.

After

a final two days in Telavi, capital of the Kakheti region,

and a visit to the Tsinandali winery, we rode on into Azerbaijan.

Although Azerbaijan is said to be poorer than Georgia, the

country seemed somehow more progressive, more looking to the

future rather than the past. Villages and cities were less

in a state of disrepair than in Georgia, smiles were offered

more readily and the mood appeared more optimistic. After

a pleasantly easy (and free!!) border crossing, we stopped

in Sheki, site of a palace and an old Karavanserai converted

into a hotel. Water and electricity supply tended to be erratic,

but the views were great, and at the Khan's palace, we had

to pose for scores of pictures with a group of Azeri students

that seemed to like our biker outfits.

The

following day, as we headed towards Baku, we met Knut Kaspersen,

a Norwegian working in Baku, who promptly offered his assistance,

organized free accommodation and generally was to make the

following days a very pleasant experience. We joined him and

his jolly group for a visit of a remote mountain village,

before taking up our new quarters in Baku, a very lively town

with some great architecture, good restaurants and helpful

people. Since we had a five-day transit visa, we only stayed

for three days, although we were sorely tempted to extend

our stay, if only to sample more of the excellent and cheap

Azeri caviar. Next time, once again.

The

following day, as we headed towards Baku, we met Knut Kaspersen,

a Norwegian working in Baku, who promptly offered his assistance,

organized free accommodation and generally was to make the

following days a very pleasant experience. We joined him and

his jolly group for a visit of a remote mountain village,

before taking up our new quarters in Baku, a very lively town

with some great architecture, good restaurants and helpful

people. Since we had a five-day transit visa, we only stayed

for three days, although we were sorely tempted to extend

our stay, if only to sample more of the excellent and cheap

Azeri caviar. Next time, once again.

Getting

on the ferry to Turkmenistan proved to be quite an adventure,

but could be solved with Knut's help, and by haggling furiously

(Initial asking price for us and the bikes: $400, reduced

to $240 after an hour's discussion). The stories we had heard

about the ferry and Azeri customs were not encouraging: From

multiple bribes to "the worst ferry in the world"

to stories about the captain refusing to let passengers off

the ship without further payments, we had heard enough to

approach the experience with caution. Lucky again: Azeri customs

were the best so far, not only did nobody ask for bribes,

but the customs officials actually presented us with a CD

and an Azeri flag as a gift. The ferry was similarly uneventful:

We were the only passengers aboard and other than a small

payment to upgrade our cabins, it was all quite pleasant.

In the

next chapter of our ongoing events coverage, we will tell

the tale of how the Marquis de Sade was instrumental in designing

Turkmen customs procedures, how to herd camels by motorcycle,

and reveal the identity of the world's greatest megalomaniac.